Our Mental House Part 4: What We Are Conscious Of

You are walking down the street on the way to the store to pick up some things you need. As you walk, you observe and think about what you observe. You gaze around from time to time as some things catch your attention. Have you ever considered why you noticed some things or have certain thoughts and not other? What was it about that person across the street that caught your attention and why did certain thoughts about them surface and not others? Why do aspects of what we observe bring forth memories of other experiences we have had yet others do not?

Why do some things hold our attention even to the point of overriding what we are actually doing? These are not questions easily answered, certainly not ones we can answer directly; however, the processes that lead to what we notice, remember and think about can be understood.

Thoughts are the mortar of our mental house, but they are not isolated “things”. Thoughts are part of the whole self, along with our physical aspects, emotional or astral body, our mental body, the soul (as some would put it) and other subtle bodies. Every thought we have manifests a reaction in all aspects of us and vice versa, though for the most part it is our thoughts that have the largest single effect on all other aspects.

We have looked at how thoughts are manifested, and some of the consequences of our thoughts to us. They establish or determine our relationship with everything and hence are our interface with the world around us, as well as with ourselves. They are the clothes our spirit wears. There is no escaping this, save if one is in a deep meditative state, so it is important that we understand the affects of individual and interconnected webs of thoughts. Understanding how we are conscious of some things rather than others can help us to examine our thoughts in new ways that lead to insights about ourselves.

As adults, we rarely use or activate individual thoughts for they are all connected in a multitude of ways. For instance, we do not think of a car in isolation, for thinking about a car brings in other thoughts such as our preferences in vehicles and their utility to us; it can evoke certain emotions, bring in thoughts about modes of transport and personal mobility and even such ideas as status and value. This means that when we have a thought, other thoughts become active as well.

The reason we have certain thoughts and not others depends on a number of factors, primarily the following:

- Our personal experiential history- What we experience shapes how our mind develops including what we react to and hence what we think about (whether we are conscious of it or not).

- How we integrated our reactions to experiences- Our reaction history determines whether we are conscious of something or not.

- Our reactions to our experiences- The nature of the thought determines how prominent it is. We are more likely to be conscious of thoughts formed out of strong reactions to experiences, or where the thought is has a large number of commonalities with other thoughts. Repetition is another way, though often this allows us to act without “thinking” about it.

- Our current experiences- Obviously our reactions to the experiences we are having now means these thoughts are likely to be the most active. However, our minds filter out much of what we experience and other thoughts can take precedence.

We will consider and examine these four factors independently; however, they do not act in this fashion. Each of the factors is influenced strongly by the others. None of these factors is independent; therefore, we will look at them individually and then consider how they combine as this is what determines whether we are conscious of a thought.

Our Personal Experiential History

That our personal experiential history is a factor in what we are conscious of should be obvious. Our experiences influence the thoughts we have. We have different thoughts because of different stimuli. The thoughts we have are a result of our experiences; however, it is also important to note that after we have developed our mental house our thoughts begin to affect what experiences we have. Some people refer to this as the self-fulfilling prophecy.

We are here to learn, hence what we experience, the thoughts we have about them and how we integrate these experiences not only affect what we think about they establish patterns that our lives follow. These are our lessons in life and this is how we built our mental house. It is also important to remember that we are born with a particular set of attributes beyond those of our physical vehicles as well as into circumstances “we chose” to facilitate our evolution.

Just as we have physical DNA, our spirits have a template of sorts that we start with. You can call this our individuality, one we then start to wrap a personality around. Initially it is our inherent individuality influencing our reactions to experiences. Once our minds have developed sufficiently we can start to use it, though unfortunately we also associate it with this construct rather than the inherent individuality that lies beneath. This is why the enlightened have suggested that "today's personality is tomorrow's individuality", because what we allow to persist eventually can become ingrained, and for more than just our current life.

We can see this individuality in the basic tendencies of a child, as any parent can tell you or as can anyone who has observed a child. We may be quiet, curious, reserved, rambunctious, needy, playfully, joyous sullen or cantankerous or combinations thereof. These are not accidents of birth. Consider how your own circumstances have shaped not only the experiences you had but also the ideas and thoughts that came out of them and how they have affected who you are.

Many fall into the trap of thinking about why life has dealt them the cards it did rather than pondering what they could learn about themselves with the hand life dealt to them. Following the former method of thinking, we get into thoughts of “what if”. Such notions do not serve us, not only do they take us away from the now; they can, for example, result in our creating imagined possibilities, ones that can make us feel worse about ourselves. It is far better for us to consider what our experiences tell us about ourselves in the now.

How We Integrate Our Reactions to Our Experiences

In terms of the second factor, we looked at how we integrated thoughts with the Experience Reaction Sequence (ERS), in the essay “Paying Attention to our Attention” (1). This is the most significant factor in the development of our mind and is the most significant in terms of what thoughts are conscious. To summarize this process, when we experience something we have initial thoughts about it. This thought activates other thoughts and so on until our mind has integrated the experience and we move on to the next one. How long the process takes depends on what the thought, and the other thoughts it shares commonalities with as well as the emotions it evokes.

For instance, when I pick up a pen, my mind does not generally dwell on the act of picking it up, how it feels in my hand and so on. However, if I see an object that is unfamiliar, the mind tries to classify it based on a number of attributes such as shape, size, colour and surface texture. What is occurring is the mind is comparing attributes of what we perceived with our memory of other objects.

This process can take some time, especially if the object does not resemble anything we have seen before. The mind will try to manifest a new thought based on how closely the object resembles other objects. Besides thoughts related to its physical attributes, we have ones about the objects potential function or uses, its value and others as well.

If the object catches our attention, for whatever reason, we may consider it for minutes, hours and even days. On the other hand, when the object is something that our minds find familiar, it can classify it almost instantaneously. Another reason why some reactions can take longer, in some cases they may never be integrated, is when the thought is activates many other webs of thought which result in conflicts.

Our minds do not let go of conflicts because conflicting thoughts continue to interact and interactions are a form of stimulus. These interactions involve many different webs of thoughts and the conflicts that arise can continue to gnaw away at the non-conscious level of our mind. This not only distracts us, it reduces our capacity to focus; this process can occur just below or on the borders of the conscious level and thereby affect our conscious thoughts.

To help you understand a little more about the integration process, I will briefly touch on the process our mind goes through during a simple experience. Let us say someone offered you a cup for a coffee they are about to pour for you. Even if the cup had an odd shape, you would not be thinking, “What is this?” The mind would know assess the attributes of the object, know it is a cup of some kind because it very quickly attributes the appropriate attributes of the group of things that are “cups” to the “cup” we were given. We would integrate this new form of cup quickly as opposed to a strange object where there is no context.

An example of this would be a situation where no one was pouring anything, and someone has merely handing you something. In this case, if the shape of the cup was different enough, we might be inclined to view the cup as a piece of artwork or we may not know what it is at all.

For instance, when we think of something such as a car, its attributes include a shape, colour and size and so on. If we were to liken these attributes to tuning forks, each being atomic thought (2), the thought “car” is a complex or composite thoughts or in this analogy, a bundle of tuning forks. In terms of a thought about “car”, there is one tuning fork for each attribute. In the case of “car”, it may also include the idea of wheels, seats for people to sit in, and doors and so on.

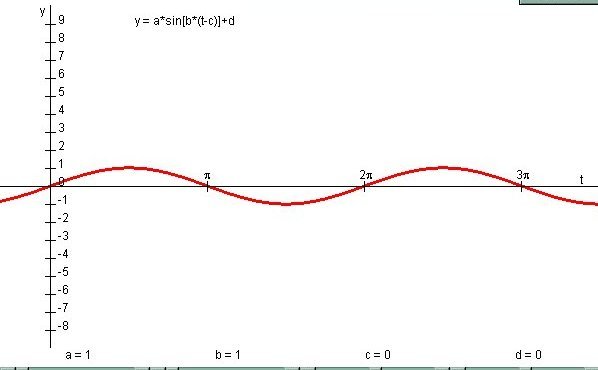

To help you visualize this, in mathematics, there is a curve called a sine curve. A sound wave is of this type. In the picture below is an example of a simple sine curve. You will notice an equation at the top, it is not important that you understand equation, though I want you to look at it. You will see that there are a number of variables in the equation. The shape of the curve, in red, varies depending on the values of the variables a, b, c, d and t. Do note that that the thought “car” is a composite thought that is it is comprised of a number of thoughts. In this example, each of these attributes would then also be thoughts.

A Basic Sine Curve

Let us say that figuratively, this curve describes a simple thought of only a few attributes (the attributes being the variables in the equation). Now, no two thoughts are alike, so even though two simple thoughts can have some of the same attributes, that is the values of a, or say d could be the same, yet the equation would result in the sine curve having a different shape. Change these values and the curve may be higher, steeper or longer.

For the sake of argument, let us say this curve represents our thought of “car”, though even a simple thought about a car would be almost infinitely more complex that the curve in the above picture. Imagine that the shape of “car” is represented by “a”, the colour by “d” and so on. When I think about “car”, the thought that comes to mind includes all these various attributes.

Now, when we have the thought “car”, any other thoughts that have the same values of say a, or d would become activated. This is where the tuning fork analogy helps. Imagine a thought as a bundle of tuning forks, one for each attribute. When we think of “car”, we are striking the whole bundle of tuning forks at the same time. Other thoughts that share the same elements (tuning forks) in whole or in part to those of the thought “car” will resonate or activated. When we think “car”, we then have subsequently thoughts such as ones about a particular car, our experiences with cars, even what we can do with a car or details about cars and so on.

The attributes of the thought “car” were determined by how integrated the thought “car” the first time, as well as how subsequent experiences have modify it. An example of this would be how our experiences change how we remember experiences that happened long ago or how our opinion of “things” can change. One last point to note is that our minds also associate thoughts regarding value; that is to say, when we like or dislike certain things and our mind captures this information. Therefore, if we originally liked some object that happened to be red in colour and over time have come to dislike the colour red, our minds integrate this new thought. As a result, our thoughts about the object, which were originally positive, can change to our disliking it.

The integration of thoughts occurs rapidly and most do not notice it occurring. This is where our conscious reasoning skills come into play. If we are quick to judge, do not consider whether our conscious thoughts are reasonable, or follow valid lines of reasoning, our mind will not apply them during the integration process. The mind itself does not base the process on reasoning, it basis it on commonalities. If we are not reasoning at the conscious level, if we go with superficial observations (which can lead to erroneous thinking) then the thought we have will not be valid. Our minds do not differentiate between valid and invalid thoughts; hence, this affects how the mind integrates the experience.

Our Reactions to Our Experiences

The thoughts and the webs they form are the basis of our mental house. What creates these webs of thoughts is the integration of experiences. As explained in “Paying Attention to Our Attention”, the mind reacts to stimulus, and this reaction becomes an experience as well. That is to say, we experience our own reaction and will do so until our mind has dealt with it.

Now, for every thought we have there is a corresponding resonance at the emotional plane; the thought has us feeling a certain way. The stronger the emotional energies triggered by the thought (or any of its attributes), the stronger it is, and the more likely it is to activate other thoughts. If someone tosses us a baseball and we catch it, we are not likely to spend a great deal of time thinking about it, unless we missed catching the ball and it hit us in the head or we made a spectacular catch.

The strength of our emotional reactions influences the prominence of the thoughts our reactions manifest. This increases the likelihood that we are conscious of them. As another example, though from a slightly different angle, let us say we have come to find long hair very attractive, when we see someone with long hair that particular attribute, the attractiveness of it can override less attractive aspects that person may have. If they did not have long hair, we might not have reacted so strongly to them. Now, this is not to say we are necessarily conscious that the reason we find them attractive is their long hair.

The strength of our reactions, and our reaction takes the form of thoughts, also affects the strength of the webs of any associated thoughts. This is how the mind can create associations where not existing, this is referred to as erroneous reasoning. In the movie Used Cars, the character Jeff has an issue with red paint on a car. The outer colour of the car he is driving is yellow and he drives it without a problem. However, when he sees red paint underneath it he freezes as he associated the red paint of the car with bad luck and trouble and refuses to drive it any further. The colour red was fine until it is associated with the colour of the car.

Our Current Experiences

Our current experiences are the most obvious influences on what thoughts are conscious ones. If I am walking outside, I am likely conscious of the weather, the conditions of the ground I am walking on, and so on. If I see a car, then it is likely I am conscious of thoughts about the car or that thought has me thinking about other cars that are similar, or nicer or faster. Having said this, just because we are experiencing something in the moment does not mean we are conscious of it. Another factor to consider is that our minds filter out information it views as irrelevant to us, we do not notice this for we do not make this choice consciously.

Our thoughts and the emotions they trigger have an enormous affect on what we are conscious of, as they tend to be the current dominant influence. Generally, the majority of our attention is on what is happening to us now, though everyone, at some point in time or another, has found they did something but do not remember doing it. This typically occurs with mundane task or actions, ones that we do not need to pay conscious attention to accomplish, we may be daydreaming as we were doing it, our minds blissfully elsewhere. Otherwise, our focus is on what is relevant to what we are doing.

It is important to recognize that, despite what we may believe, our rational mind is rarely in the moment. We have goals, destinations or tasks on our mind; that is when we are not thinking about what we will do later, what we have just done or are doing or what we would like to be doing. Most of these revolve around our current activity, that is to say we are reacting to our experiences. The thoughts we have about our current activities provide a form of fulcrum for other thoughts to revolve around.

We have now looked at the major influences on what we are conscious of at any point in time. None of the above factors is sufficient to explain why we remember some things and not others, nor what thoughts we are conscious of when we have an experience.

A friend of mine once likened how our minds operate to the conveyors that move baggage around for pickup at an airport. Imagine a network of conveyor belts, countless miles of them interwoven and only a very short section passes out to where you pick up your luggage. This part would be synonymous with our conscious mind. Only a very, very small portion of the convey belt is visible outside of the wall (we do not see the baggage handling area), similarly, we are aware of only a very small subset of our thoughts. This is not to say that we cannot be aware of more, only that for the most part we are not. So, how does our mind determine what is visible out in front of the wall?

It does so due to a combination of all of the factors we have touched on. Our experiences have led to our manifesting different thoughts, thoughts that our minds process via integration. Each thought we have is also an experience and has attributes that describe it. Further, associated with each thought are the feelings each attribute manifests and there is the experience as a whole.

The integration process results in webs of interconnected thoughts due to commonalities between the attributes of the thoughts. The strength of our reaction and the values we assign to it (like or dislike for example) are also part of the thought and affect its integration. Finally, we have our present circumstances and the stimulus that is occurring “now”.

In the moment, our minds are processing what we experience. Not just some of it, it processes every stimulus that we perceive (and we perceive what we are capable of reacting to). If each thought is a piece of luggage on the conveyor belt, those that reach the conscious level are the ones we have trained or taught our minds to pay attention to because they matter to us. By matter, I mean we have made them important. If we are preoccupied with other thoughts, then what is occurring now will be of less importance and hence other thoughts will be filtered out, that is our minds will not place them on the portion of the conveyor belt that leads them outside the wall. If we feel strongly about something, and have not told our minds “we do not want to know about it”, our minds are more likely to present these thoughts to us.

It is not rocket science, we are creatures of habits, and we train our minds with every experience we have. When we casually think a thought such as “I do not need to know about this” and we do this often, we are telling our minds that we do not want these thoughts to appear outside the wall; and this is what it does. Contrary to popular notions, ignorance is not bliss.

There is no formula one can apply to determine what thoughts are conscious ones and which are not. Nor is this the point of the essay. The point is to get you thinking about what is going on in your mind whether you are conscious of it or not. Where this is most relevant is when we examine our lives and ourselves through our reactions to what we experience.

If one is working on their personal growth, and is trying to unravel a particular issue in their lives, understanding the connection between our experiences and our reactions to them and thereby the experiences we attract is very helpful. When we run on autopilot, when we are going from experience to experience we have little control over our lives, though control itself not what we seek. What we seek to do is to ensure that our minds are not controlling us. Paying attention to what we are conscious of does help us to start to unravel the mystery of our minds. It is invaluable to help us to understand what our minds are doing on our behalf.

They say, “Be careful what you wish for”, and not without good reason. It is not a false statement, for our minds cannot differentiate between conscious thoughts and those that are not, just as it does not differentiate between what we do and what we imagine. It is merely doing what it does whether we pay attention or not. We see what we want to see, even though we do not remember how nor even deciding what we want. We experience what we need to experience, even though we do not know how this need is determined.

We must start to grasp that imagining the future is not always helpful just as living in the past keeps us locked into what was. If we make our imagined future important or events in the past then these are going to be thoughts we are conscious of regardless of what is happening around us. Certainly one needs to consider the future; however, the tendency is to imagine an unrealistic future especially when we are unhappy with our current circumstances. To imagine the future in such a fashion is to create an illusion that takes us away from “now”. It is also possible to become so enamored with our imagined future that we focus our attention there, rather than on what we are doing or need to do.

As I mentioned, all of these factors affect whether we are conscious of a thought or not. Our minds create strange webs of thoughts based on our reactions. Which ones are active at any point in time depends on the factors I have mentioned. We do not consciously control this, because it is complex and difficult to do so and because we have long since abdicated control.

Ultimately, it is each of us that has given the power to decide to our mind, so it is up to each of us to wrestle back control from it. It is easy to go on autopilot rather than to be fully cognizant in the moment. We become unable to be present in the moment as our minds keep feeding us thoughts that we have trained it to find important. We would rather live in our imaginings than in reality though few of us would like to believe this could be true.

This essay only scratches the surface of this topic; though my hope is that it is sufficient to give you a better understanding of how the mind works. Next time you start thinking about something negative or that brings you out of a peaceful state of mind do not simply try to dispel it. Consider it; ask yourself why your mind might see this as more important than what is going on at the time.

We can use this same thought process to help ourselves develop our attention and focus. How you ask? Simply because the reason we are unable to focus at a particular time, is other thoughts have taken precedence. They may be thoughts just on the border of our conscious attention, but they are there else we would be able to focus our attention. We will not become aware of what they might be without stopping to notice. This can be inconvenient at times, yet if we are intent on growing, we cannot put it off and still expect to make positive change for ourselves.

End of Part 4

==> Continue to Part 5: The Affects of Our Thoughts

© 2012 Allan Beveridge

References: